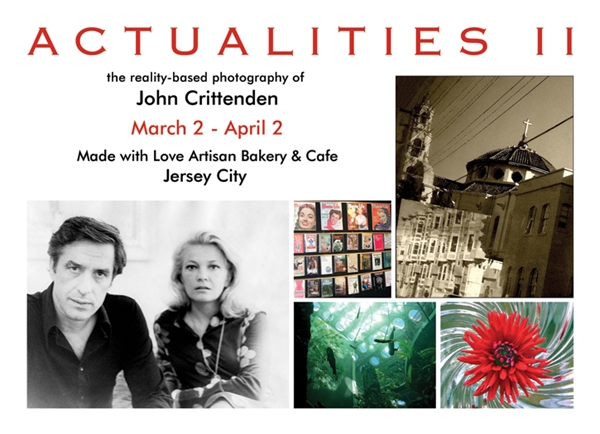

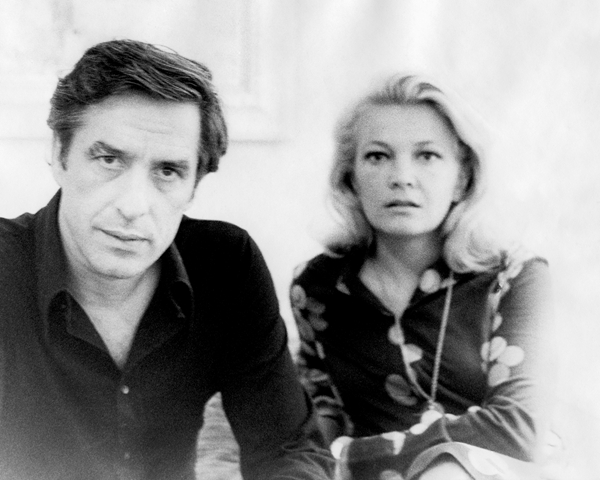

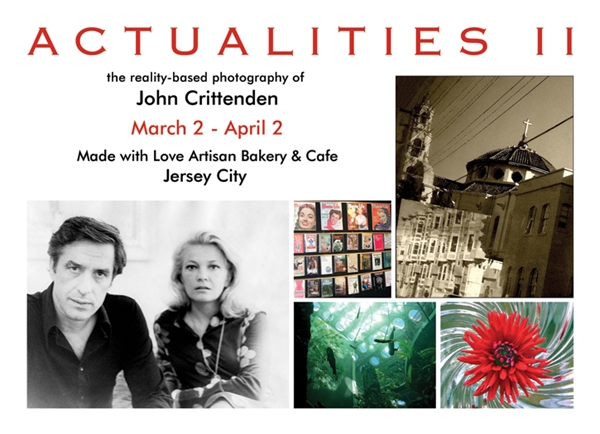

I’m pleased to be having my second solo show, less than a year after my first, at Made With Love Artisan Bakery & Cafe in Downtown Jersey City. Included in Actualities II are my portraits of John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands, Liv Ullmann and Judy Collins, taken in the mid-1970s when I was a young journalist.

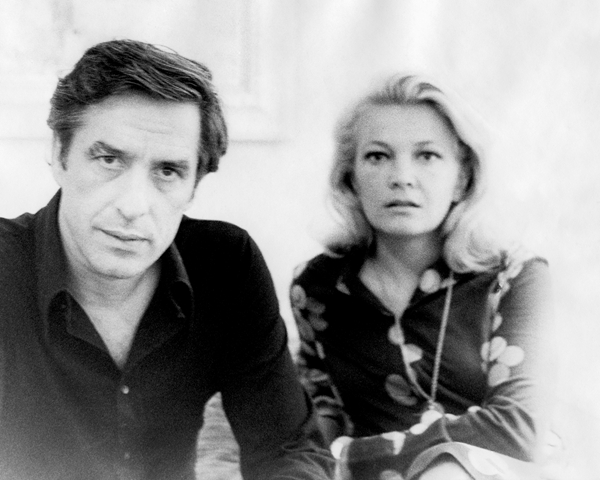

I was lucky to secure the 9 a.m. slot to interview John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands the morning after “A Woman Under the Influence” — many consider it to be the greatest of the films they made together — debuted at the 1974 New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center. The interview was done in their hotel suite on West 58th Street, and they were still waking up when we began. He appeared first, and soon she came into the room and he presented her to me with admiration and pride in his voice. She seemed shy, almost fragile, and was even more strikingly beautiful than when acting on screen. At the end of the interview, I pulled out my Minolta 35mm film camera and took a few pictures without missing a beat. Having chatted for the better part of an hour, they were comfortable, weren’t asked to pose, and I didn’t use a flash. There was plenty of soft incandescent in the room and morning light was coming through the curtains. And so I captured the images of the director now remembered as the father of independent film in America, as well as a fine actor, and his actress wife, who is still beautiful and still making interesting movies today.

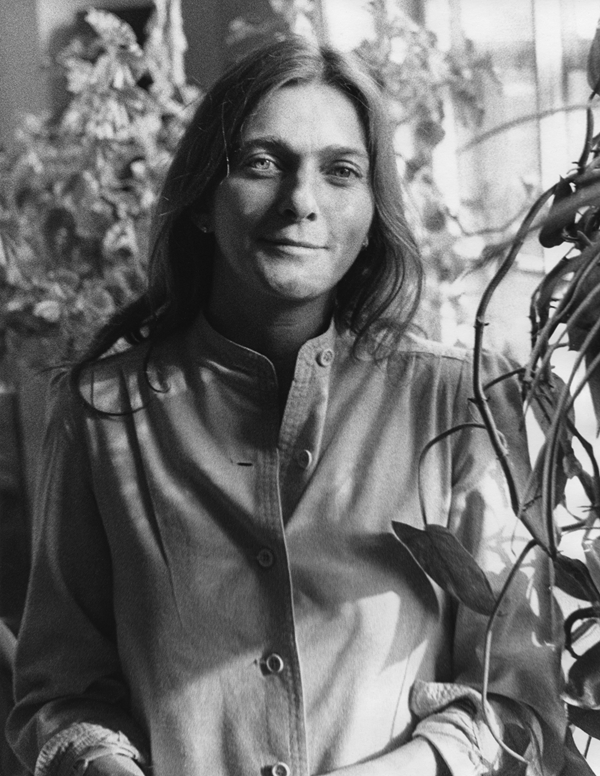

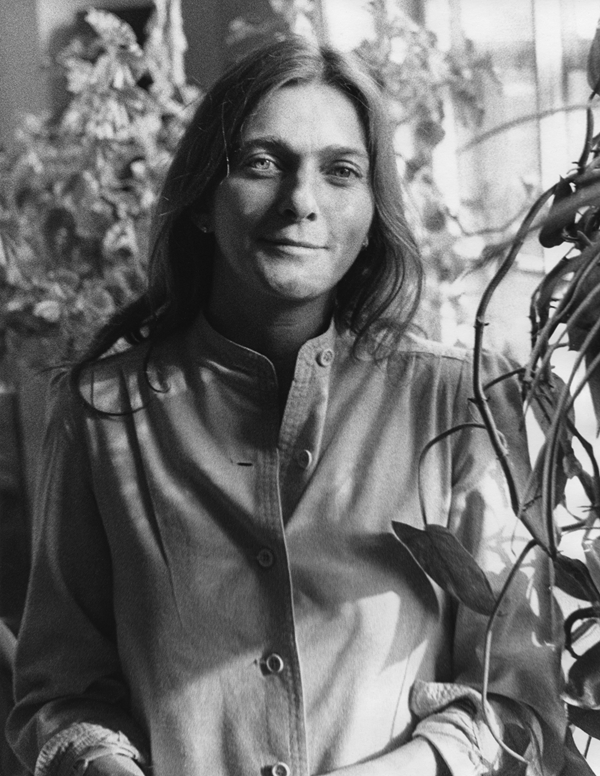

Judy Collins welcomed me into her apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side to discuss a film, “Antonia: A Portrait of the Woman,” which she produced and Jill Godmilow directed. The 1974 feature documentary tells the compelling but not widely known story of Antonia Brico, who in 1938 was the first woman to conduct the New York Philharmonic.

Born in The Netherlands, Brico grew up in California and was an accomplished pianist when she left high school, and already had experience in conducting. She graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1923 and in 1927 entered the Berlin State Academy of Music, becoming the first American to graduate from its master class in conducting. She debuted as a professional conductor with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in 1930. In 1934, back in the States, she was appointed conductor of the new Women’s Symphony Orchestra, which in 1939 became the Brico Symphony Orchestra after it admitted men. She conducted at the New York World’s Fair. But there were discouragingly few opportunities.

In 1942, she settled in Denver, Colorado and spent the rest of her life there, founding several local musical groups, conducting the Denver Symphony Orchestra, playing a major role in the city’s cultural life. She also taught piano, and this is where Judy Collins met her. She was one of Antonia Brico’s piano students.

I think it was extraordinary that Judy Collins, whose own musical career was going full swing in 1974, invested time and money in making a film tribute to a woman who was a hero in her life and who, she felt, had not gotten the artistic recognition she deserved in a field that was, and still is, predominantly male. And Judy Collins made sure the film was done right. “Antonia: A Portrait of the Woman” was nominated for an Academy Award in the documentary category. Antonia Brico died in Denver in 1989, at age 87.

After our interview, I photographed Judy Collins among her houseplants in her south-facing living room. Our visit was a particular thrill for me, of course, for hers was and is one of the great voices of my generation, and that interview was done only seven short years after her album “Wildflowers” was on every turntable in every college dorm room in America, including my own.

These photographs were taken in San Francisco, a city I dearly love. “In the City of Saint Francis” is on the right, a sepia-toned rendition of a single image. I think it has some feeling of the movement of the bus I was on when I took the exposure. I knew we would soon pass Mission Dolores, a tiny adobe church built in 1791 and the city’s oldest surviving structure, and I wanted to ready to snap it. I was shooting wildly, wondering what images I might get, kind of priming the camera. It turned out that this was the more interesting shot, a lucky shot totally unplanned. It’s a bit off-putting in color, with a phantom red digital zipper of words running through the middle, but when I took the color out and saw it in black and white I knew I had something. The lower left section of the image is the reflection in the bus window of the line of bay-windowed apartment houses across the street. The large church building with the cross on top is the modern basilica of Mission Dolores Church. Altogether, it is a vision of the city as it has looked, in this spot, for more than a half-century.

The subject is popular media in the photos at left, which are printed on metal and “float” on the wall, their corners as sharp as any print. Artists working in all mediums are fashioning comments these days on the supposed end of the print era, and these are mine. The relatively benign movie magazines from the 1940s and ’50s and the paperbacks with eye-catching covers displayed below them in the top photo were in the window of a used book store on Post Street. The magazines in the lower photo promise us, in January 2010, the latest “misery” in the lives of Jennifer and Brad and Angelina, none of which seems to have come to anything. I guess news was slow that week, the competition as cut-throat as ever. Whether such pages will still be viewed in one’s hands in 10 years time or will only be seen on screens I do not know. But I’m sure celebrity culture will continue to serve up the same formula “inside” exclusives. Inquiring minds will always want to know.

I’ve always been deeply ambivalent about the real place called Hollywood and about Los Angeles in general. When I first flew out for a visit, about 1970, I had a window seat and during our low approach to LAX I looked out over mile after flat mile of superblocks divided by major streets, all viewed as if through a light chartreuse filter. This was before clean air laws and mandated emissions controls on cars. The air burned my eyes on two occasions during my week-long stay, and I wondered how so many people could live there seemingly satisfied with conditions I could hardly tolerate. Fast forward about 40 years and I’m still not in love with L.A., but I do manage to have fun when I’m there.

This photo was snapped in February 2007 during the week before the Oscars were handed out. Hollywood Boulevard was closed to traffic for many blocks around the Kodak Theater, creating snarls and backups on all the other major roads, but I was able to find and park in one of three lots adjoining the back of the Hollywood Wax Museum so I could attend one of the screenings in a festival showcasing new Italian films at Grauman’s Chinese, on the same crowded block as the Kodak. When I got back to the car, night had fallen and the lights were on, and I knew I had to preserve this vision of Hollywood, a company town where billboards touting new product seem bigger and more numerous than anywhere else in the world, and where every actor hopes to achieve the immortality of John Wayne, Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe, Charlie Chaplin. I was especially taken with the way the museum’s mural incorporates the utility lines on the sides of the building. Nothing gets in the way of promotion in Tinseltown.

Just after New Year’s, when Celeste Governanti, the proprietor of Made with Love Artisan Bakery & Cafe, invited me to mount a photography show in the far-off month of June, she asked if I could include one or two things that related to Fathers Day. Hmmmmm, I wondered. I’ve never really done genre photos — I’ll let someone else do greeting cards and stock photos of beaming models and rented offspring. Still, I had a request to fill and I kept it in the back of my mind. Soon I was off to San Francisco for the Noir City 8 Film Festival at the Castro Theater, and while I was having a late breakfast between Sunday screenings of bank heist and blackmail melodramas in glorious 1950s black and white I noticed two dads and their daughter at the next table. They live in Oakland, have been partners for eight years, and were having brunch before taking Amelia to Samoan church for an afternoon service. I promised them a family smile shot, which was easy to snap against a fancy grilled doorway next door to the restaurant on busy Castro Street, and also posed them under the huge rainbow flag that flies above Castro and Market. Then we all looked down Market Street, with its palm trees and signs and street car cables and traffic — the reality of life there. Our shoot took only 15 minutes and their family has two portraits and I got a Dads Day shot for my show. I call this “Fathers Show Us the Way.”

Some weeks later, I became acquainted with a couple in my neighborhood who have a little boy who’s just graduated from being a rug rat to zooming around on his own two feet. I’ve had this setup in my mind’s eye since seeing it in another photographer’s display a couple of years ago. I don’t feel at all guilty about stealing his idea; he probably stole it from someone else. Besides, the feet in his shot were so perfectly lovely, so sentimentalized, so “commercial.” I’d never do that, and I haven’t. This shot was taken Memorial Day afternoon at the park at the end of the block. The boy’s feet will never again be this small as he grows and grows and grows, and he’ll always have this picture as a memento of his babyhood. No doubt that he’s with Daddy. I call it “Tootsies.”

And here’s how “Tootsies” looks in the window at Made with Love. The family adores it, and so does Celeste. Fits perfectly with Fathers Day, doesn’t it.

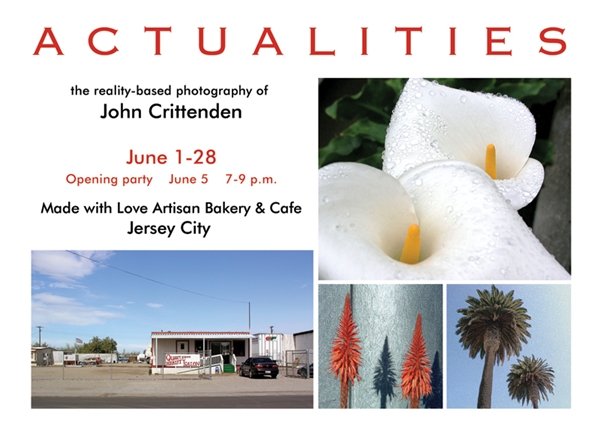

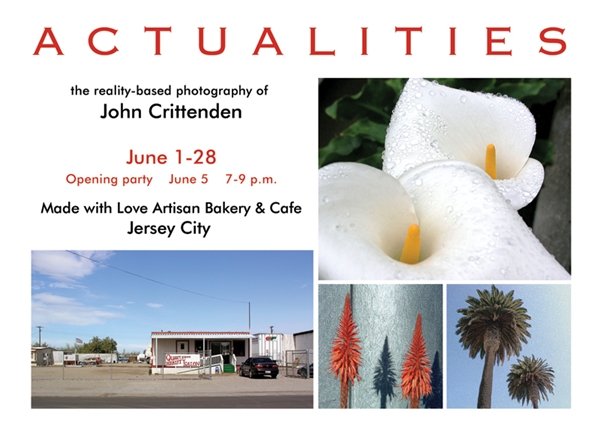

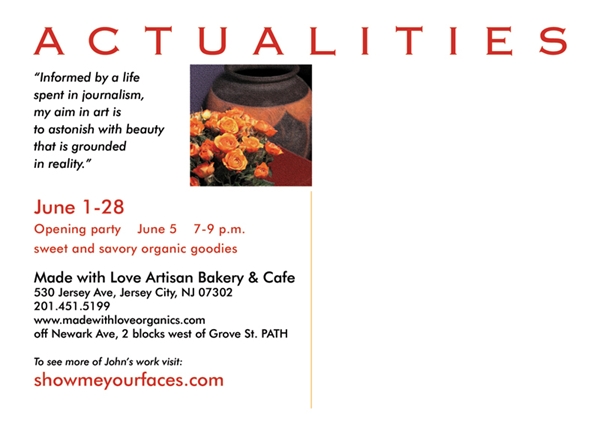

You’re invited to my first solo show, on the walls during the whole month of June at Made With Love Artisan Bakery & Cafe, in Downtown Jersey City. An opening party is planned for Saturday, June 5, from 7 to 9 p.m. Susan Newman designed my postcard.

We’re a fan of good headlines. I spend a good bit of my work time each week writing them for a daily newspaper, and in fact I’ve just taken first place — for the second time — in the New Jersey Press Association’s Better Newspaper Contest in the Best Headlines, Newspapers Under 60,000 Circulation category. I can’t claim the one on this post, though; it popped up recently in The New York Times on a review of a book about taxidermy. It reminded me of these pictures I took on Haight Street in San Francisco in late January. Photographing through a window is usually not recommended. You often get unpredictable glare, reflections, and may end up with a photo of yourself taking a photograph. But if you are careful, you can capture a magic memory. Loved to Death is a curiosity, taxidermy and vintage everything store. The more usual deer and elk heads are inside. It’s not the kind of shop one happens by every day.

While selecting photographs to show in the 2009 Vital Voices exhibition in the Jersey City Artists Studio Tour, the influence of three master photographers seemed obvious. I’ve loved their work for decades, so I wasn’t surprised. There’s not a photographer alive whose vision has not been influenced, either directly or indirectly, by their ways of seeing.

“The Quartzsite Beauty Salon, Quartzsite, Ariz.” – The town of Quartzsite, pop. 3,354, is in western Arizona near the California border. A popular RV camping ground for winter tourists, its gem and mineral sellers and more than a dozen general swap meets attract more than a million people a year to the only town on the interstate between Phoenix and California. It was a bright February day when I stopped there for lunch at a just-the-basics restaurant, and across the street was a beauty parlor waiting for business to walk through its door.

Revered for finding quiet beauty in unadorned people and small-town architecture, Walker Evans was born into wealth and was educated at Phillips Academy and Williams College before dropping out and spending a year in Paris, then joining the New York art crowd. He is best known for documenting rural life and poverty during the Great Depression for the Farm Security Administration. His book with the author James Agee, “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men,” focused on three sharecropper families in southern Alabama, was published in 1941. His 1938 show at the Museum of Modern Art was the first the museum devoted to a single photographer; it staged another comprehensive exhibit in 1971. Walker Evans died in 1975, having spent several years teaching at Yale after writing and editing for 20 years at Time and then Fortune magazine. Except for 1,000 negatives owned by the Library of Congress and in the public domain, the Metropolitan Museum of Art owns the copyright on all of his works in all media. He is quoted as saying his goal as a photographer was to make pictures that were “literate, authoritative, transcendent.”

“Calla Lilies, San Francisco, January 2009” – It was raining when my plane landed and in my first walk around my friends’ neighborhood I spotted these callas, still wearing raindrops, growing in a cement trough squeezed between the driveway and front staircase of an otherwise ordinary home.

Considered the quintessential woman photographer of the 20th century, Imogen Cunningham’s first job out of college in 1907 was making platinum prints in the darkroom of Edward S. Curtis. The photographer whose work documented the lives of the various North American Indian tribes operated one of the most successful portrait studios in Seattle. Cunningham’s independent college study had focused on chemistry and optics, as photography was such a young medium that there were no courses discussing “vision” or “expression.” It was Pictorialism – doing in dreamy, soft-focus photos what painters had been doing – that was the dominant photographic style. Always on the cutting edge even as she raised three children and operated her own successful Seattle portrait studio, Cunningham by the early 1930s was a leading Modernist photographer, a co-founder of the Group f/64, which valued sharp focus and helped bury the Pictorialist style, and her iconic studies of magnolia blossoms and other flowers, as well as nudes, movie star photos for Vanity Fair, and industrial landscapes, moved the medium during the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. In 1945, Cunningham accepted a teaching position in the first fine art photography department at the California School of Fine Arts, and continued to take photos until shortly before her death at 93 in San Francisco in 1976.

“The Pennsylvania Woods” – In my photo shot from a walkway at Falling Water, the Frank Lloyd Wright house, we are looking down, across and up into a wilderness area that is under the protection of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

From the 1940s through the 1970s, Eliot Porter’s nature photography set new standards in color photography, and in presenting the natural world, at a time when most “serious” photographers were limited to black and white and color was considered “too literal.” Porter’s entire body of work, and in particular his first book for the Sierra Club, “In Wilderness Is the Preservation of the World” (1962) with text from Henry David Thoreau, gave early momentum to the modern conservation movement. Porter died at age 89 in 1990, and bequeathed his professional archives, containing 10,000 prints, 84,000 color slides and transparencies, and 4,400 black and white negatives, to the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. A biography and a review of a book about Porter can be found here.

Some people don’t like old pictures of themselves, but I enjoy looking back. This was snapped with an Instamatic outside the Conservatory in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco in 1975. I remember it like it was yesterday. This is a pleasure of age that the young can’t quite comprehend.

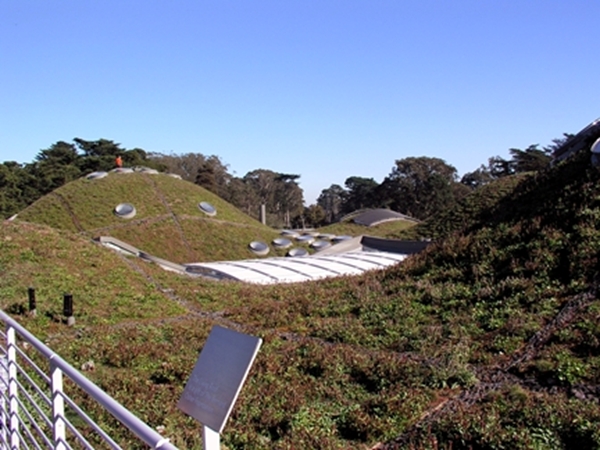

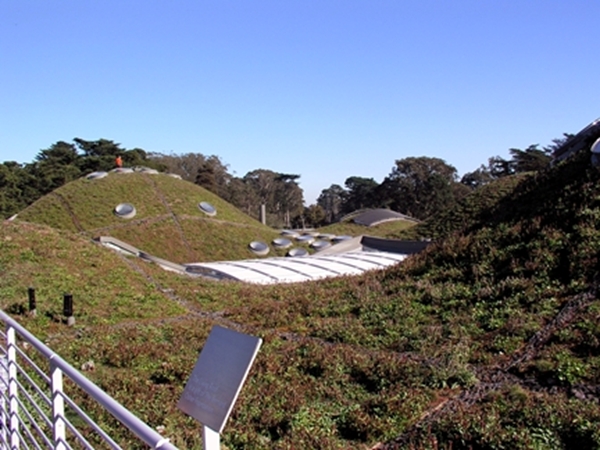

An artist friend just yesterday noted that the Huffington Post has done a “green” story http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/09/08/five-fabulous-green-roofs_n_268638.html on building roofs that are planted with all sorts of grasses and gardens. Rockefeller Center here in New York has one that’s pretty traditional — a formally structured set of garden rooms high in the sky. Also mentioned in the article is my favorite, the top of the new California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. Open since October 2008, this extraordinary complex is the natural history museum for our time and replaces the old aquarium in Golden Gate Park, sited just across from the beautiful new DeYoung Museum. When I visited on a weekday in late January, it was packed, still very much a hot ticket for locals as well as tourists.