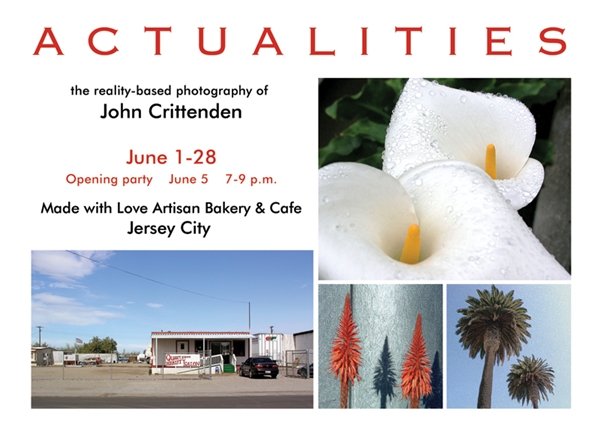

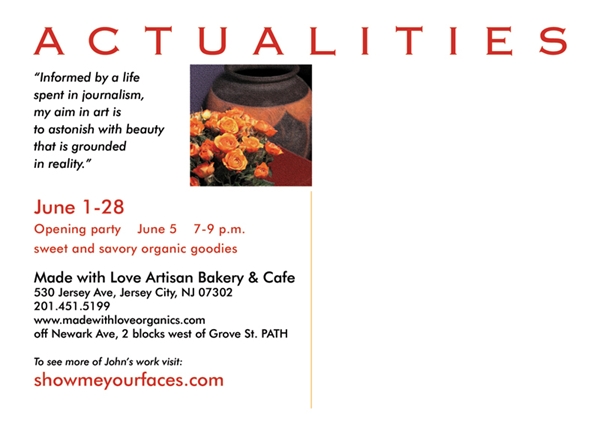

You’re invited to my first solo show, on the walls during the whole month of June at Made With Love Artisan Bakery & Cafe, in Downtown Jersey City. An opening party is planned for Saturday, June 5, from 7 to 9 p.m. Susan Newman designed my postcard.

The Distillery Gallery & Artspace opened Saturday, March 20, on Hutton Street just off Palisade Avenue in Jersey City. The space is a former garage located behind the Palisade Wine and Spirits store, also owned by Bhavin Patel, which has been a neighborhood asset for several years. Irene Borngraeber put the space together and has curated the first show, Splice, which will be up until May 1. The opening featured a sound and media performance by Gocha Tsinadze and Eto Oro titled “the waiting,” some good wines for tasting, and samples from a new Jersey City-based business — Spicy Sue’s medium and hot salsas — presented by Sue herself. The good vibes could be felt all the way around the corner and down the block. This is just the kind of gathering space, not to mention art venue, that the Jersey City Heights has been needing. It’s a pleasure to welcome it to the neighborhood.

Hiroshi Kumagai, a Newark artist whose work i’ve admired before, has work on display in this inaugural show at The Distillery. Working from photographs, he creates large, colorful works with hand-cut vinyl pieces. His work is also being seen through April 2, 2010, in the “Broken Dialect” show at the Index Art Center, on Broad Street, in Newark.

I don’t know that I’ve ever read much rock music criticism. I guess it’s like all writing about art — it helps readers find what they may not have known they wanted to listen to, helps win recognition for new artists, creates buzz – but once you know who moves you reading words and analysis can seem very beside the point.

Case in point: Leon Russell. I just ran across a quote on the Internet from Robert Christgau’s Record Guide (1981) review of the singer’s 1970 debut album as a single artist (backed by pals Harrison and Starr, Wyman and Watts, Clapton) that says that while his singing is “distinctive, and valid, it grates,” and that the album’s impressive songs would be more so if someone else were doing the vocals. Calling the album “weirder than you would expect,” Christgau gave it a B+. Well, thanks for listening, I guess.

Myself, the moment I heard Leon Russell would be headlining Hoboken’s Art and Music Festival this past Sunday afternoon, appearing at 4:30, I knew where I’d be, rain or shine. The first few hours of the festival did feature rain, and after it stopped the sky stayed gray and heavy, which cut attendance and seemed to keep smiles at a minimum, but the open tent at the foot of Washington Street wasn’t big enough to hold the appreciative crowd that loved what it was hearing.

Leon at 67 has lost a lot of the bounce he had 40 years ago; time does that. He sat fairly motionless in his Hawaiian shirt and white cowboy hat, and behind big shades. But his hands were moving up and down the keyboard and his mouth was at the mic, and the four much younger men he had with him, each a fine musician in solos, provided the visual oomph, the guitars and drums and backup vocals. The voice the noted critic took exception to so many years ago is still strong. Russell still owns every one of his hits. “Rollin’ in My Sweet Baby’s Arms,” “Georgia On My Mind,” “Delta Lady,” “Wild Horses.” And lots more, all rendered with maturity and majesty and fun.

I realized I hadn’t heard what’s categorized as Southern rock in so long I’d almost forgotten its power. In fact I was primarily there because I needed to hear him sing “A Song for You,” and until I heard it and a lot of mist got in my eyes I had indeed “forgotten” why. A friend who’s now gone home to Australia used to sing it in piano bars every time she was asked, and she was usually singing it to one of my best friends, her partner, now gone. I love the both of them “where there’s no space and time.” And on stage, Leon Russell was alone now and he was singing that song for us.

Then the younger guys came back and they all did “Roll Over, Beethoven” and “Good Golly Miss Molly,” and some other hits other people had way back when. Which was only natural, since according to one biography on the Internet Leon Russell was about 15 when he was lying about his age so he could tour in support of Jerry Lee Lewis. He’s come a long way from Lawton, Oklahoma, where he was born and started studying classical piano at age 3. A success in the music biz long before he became a star, he was the arranger of Ike and Tina Turner’s “River Deep, Mountain High” as well as a member of Phil Spector’s studio group and a collaborator with the Rolling Stones. I know a lot of people are glad Hoboken was one of the stops along the way in a long life filled with music that rolls like a river.

Maybe it’s because I grew up in Kansas, where it is the state flower, but I love every sunflower I see. And yet I’ve never tried to grow one; there’s no spot in my garden that’s right. Luckily, Jersey City Heights has lots of sunny front yards where they do grow tall. Just yesterday, I found there’s a 6-footer in front of a house across the street. Voila! Does seeing it make you as happy as it does me?

I’ll always photograph panoramas like this, which I call “The Passaic River Flows: Indians, Farmers, then Industrialists and Neglect, Now Rebirth.” Such landscapes contain stories and relationships that words and statistics piled together, even with great skill, cannot convey. The Passaic River meanders along through New Jersey for 80 miles, and its Great Falls in Paterson once ran that early city’s silk mills and are still considered a scenic wonder, but just before the Passaic empties into Newark Bay it flows through one of the most urbanized and industrialized areas in the nation.

Only 400 years ago, before Henry Hudson and the Dutch came, the Lenni Lenape Indians fished its waters. Only since the early 1970s have there been efforts to clean up the river, and the water quality is still not great, though high school and club rowing crews have been using it for decades. Certainly no commercial fishing is allowed and no one is supposed to eat anything they catch in the lower stretch of the river. For more than a hundred years factories lined the river, operating 24/7, and dumped all of their waste into the water. Just google Dioxin and Diamond Shamrock and Agent Orange for a few facts about what still lies in the river’s sediments.

In my photograph, Newark is on the left, Harrison on the right. Newark has redeveloped many acres over the past decade or so; the New Jersey Performing Arts Center is visible, as is an improved McCarter Highway and a light rail system. Harrison is busy, too, with condos and commercial buildings going up and a world-class soccer stadium under construction for the Red Bulls where acres of old red brick factory buildings once stood.

I don’t know of any other American landscape that’s gone from pristine ecosystem to total heedless exploitation and degradation, then been an abandoned wasteland for decades before ultimately seeing as much rebirth.